The value of theoretical science

the guardian, 8 Dec 2020

From Newton to Maxwell to Penrose, Britain has always excelled at theoretical science—so why doesn't the government do more to support it?

From electromagnetism to quantum mechanics, the greatest scientific discoveries often require little more than a blackboard, a stick of chalk and a congenial place in which to think. The breakthroughs of Roger Penrose, who was recently awarded a Nobel prize for his work on black holes, are a case in point. The British theoretical physicist has made discoveries in areas ranging from the fabric of spacetime to human consciousness. His “Penrose tiles”—two shapes that cover a surface in a never-repeating pattern—aren’t just lovely to look at; they have deep links to the structure of quasicrystals and the theory of computation.

Penrose joins a long line of British theoretical scientists stretching back four centuries, from Peter Higgs, GH Hardy and Paul Dirac, to John Dalton and Isaac Newton. But despite the country’s strength at producing theorists, the field of theoretical science receives little support from the UK government.

To appreciate the value of theoretical science, let’s clarify what distinguishes it from experimental science. In the latter, scientists test what they think they know about the world against the way it actually works. This is done by trying to falsify hypotheses with experiments. If a hypothesis stands up to these tests, it’s accepted as a theory. As more theories are accepted, they restrict the possibilities for newcomers. This is like searching for an answer in a crossword puzzle; when you have some of the answers, you can begin excluding many possibilities. Sometimes you can even deduce the correct word without reference to the clue.

Theoretical science is the use of mathematics to establish laws of nature and their testable consequences. It helps speed up the pace of science because it narrows the focus on what needs to be investigated. As Leonardo da Vinci put it, the man who proceeds without theory is like a sailor who enters a ship without a compass. A laconic Russian proverb makes a similar point: “Measure seven times, cut once.”

The trouble with British science is that we measure once and cut seven times—or rather, as it turns out, 14 times. An analysis of the 4,270 active grants awarded by the UK Research Councils shows that a mere 7.3% of £2.8bn research funding went to projects in the theoretical sciences. The lion’s share was lavished on experiment.

If we turn from grants to long-term core funding provided by the research councils, the picture is even worse. Of the 24 research institutes that receive core funding, only one, the Alan Turing Institute, is dedicated to theory.

The rest goes to centres for experimental science: biomedical labs, observatories, reactors and geological surveys. The US, by contrast, has 20 institutes specialising in theory, such as the Santa Fe Institute and the Institute for Advanced Study. Germany has nine, including several Max Planck Institutes.

One reason why governments favour experimental science is that it can be seen. Inconveniently, theory is invisible. Politicians may assume the public is more likely to approve of a lofty telescope, which they can see, than a law of nature, which they cannot. Another reason is that experiments are easier to understand. A hypothesis is being tested or a phenomenon observed. This is something people can get their heads around. By contrast, many areas of theoretical science require years of study to comprehend.

Finally, governments are by nature shortsighted. Electoral cycles are fleeting compared with the time it takes for fundamental breakthroughs to make their mark. Politicians assume they’re more likely to be voted back in if they favour initiatives they can point to and say: we built that.

It’s not clear that they’re right. The best-known films about science in the past decade—The Imitation Game, The Theory of Everything, The Man Who Knew Infinity – are all about theories, not experiments. Hollywood may understand something that politicians don’t: the public has a deep interest in the power of ideas to transform how we understand reality.

Scientific theories may capture our imagination because they are hard to comprehend. There’s magic at work with the theoretician, who conjures up insights from within. There’s also the glamour of the maverick theorist challenging the consensus without the apparatus or support network of the experimentalist. This is analogous to the idea of the lone artistic genius. The theoretician is the artist of science.

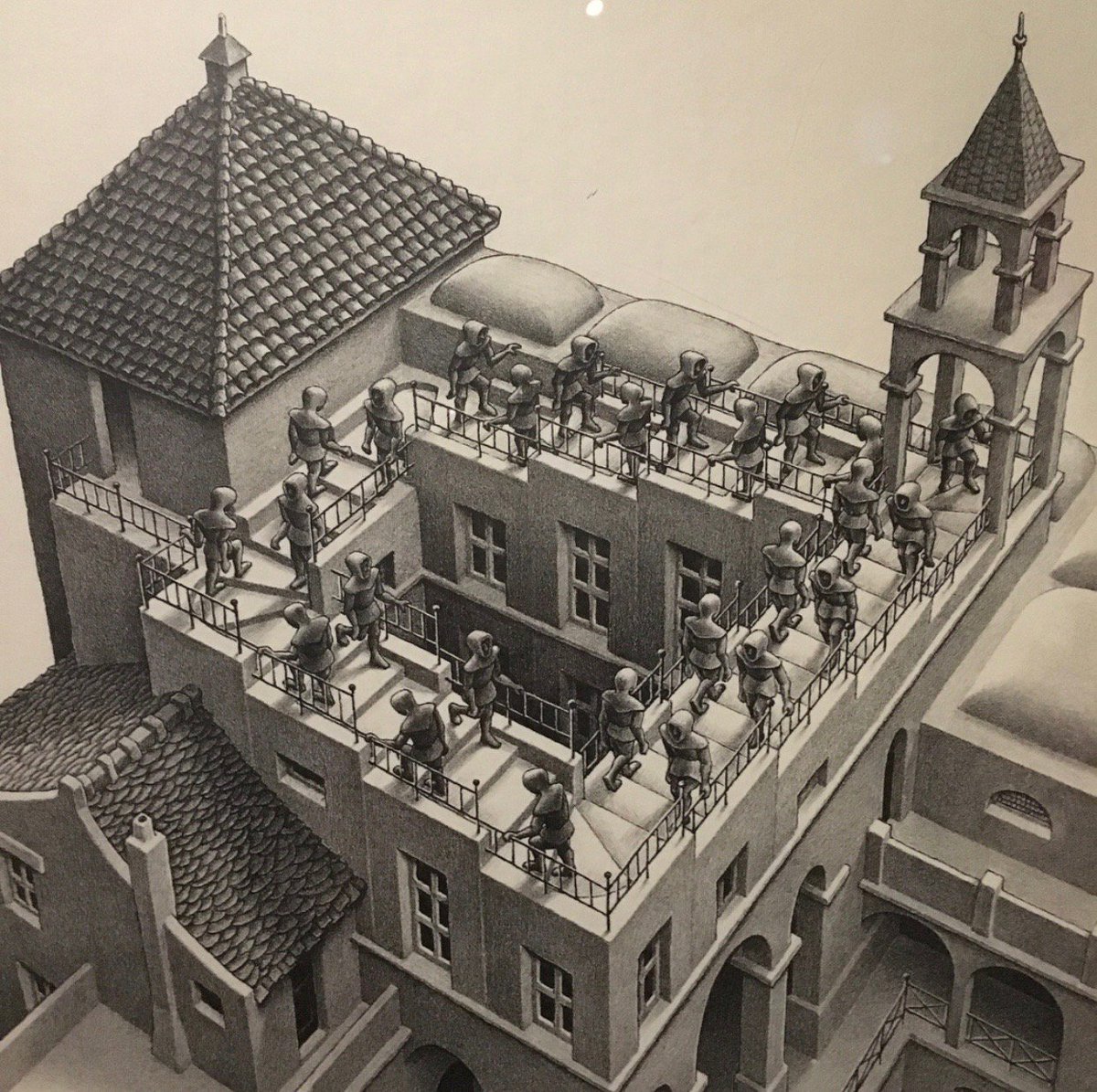

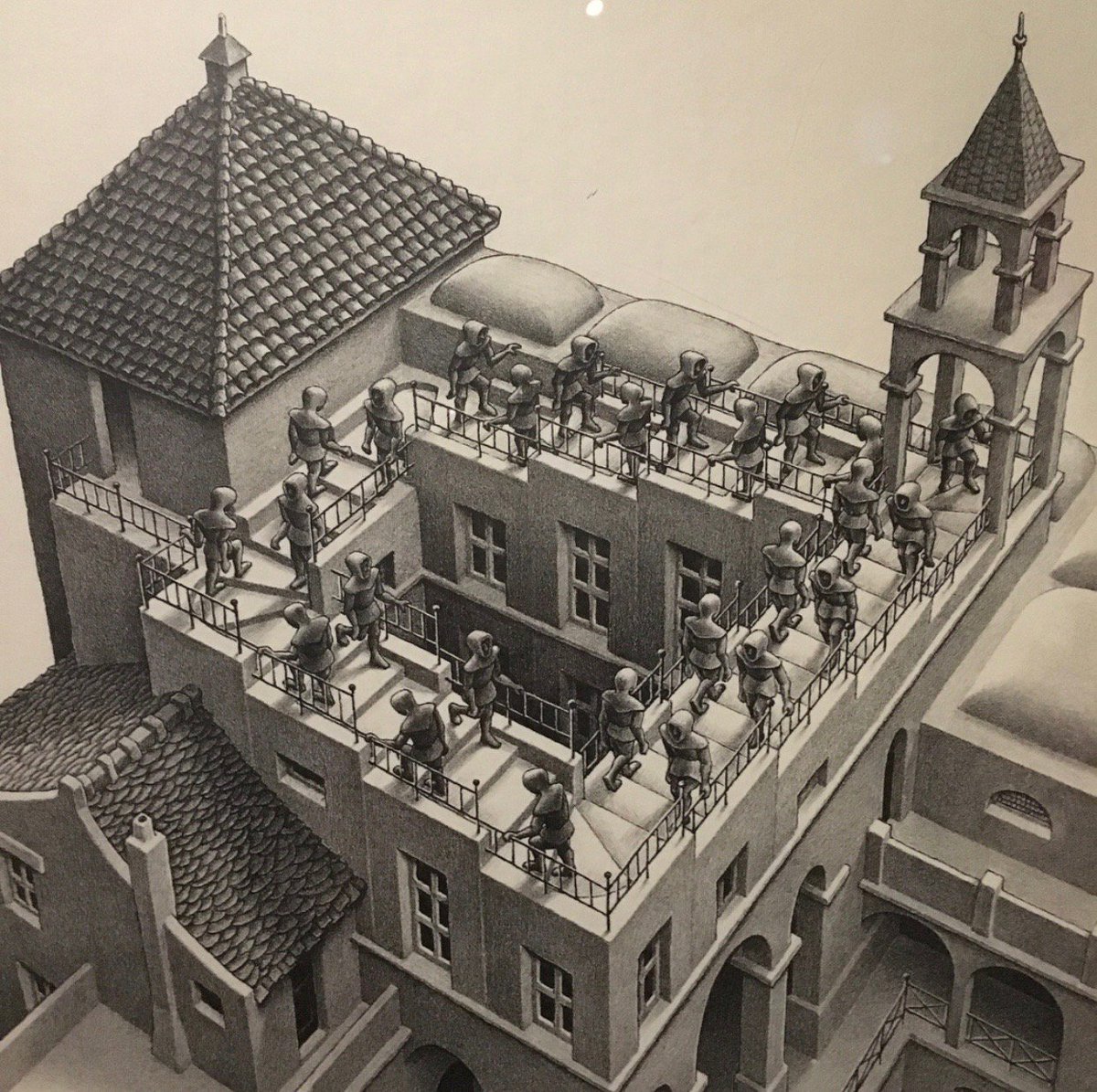

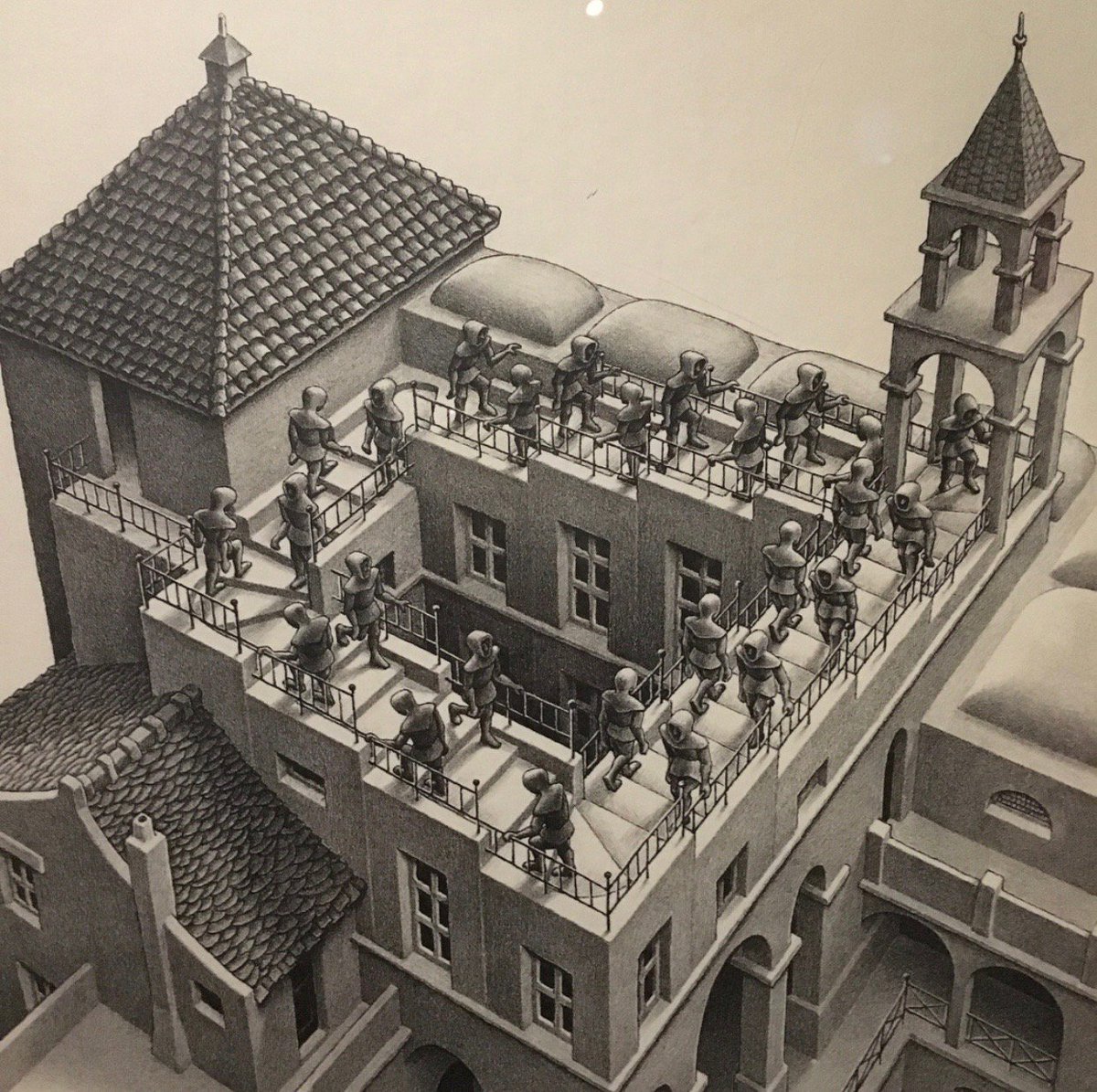

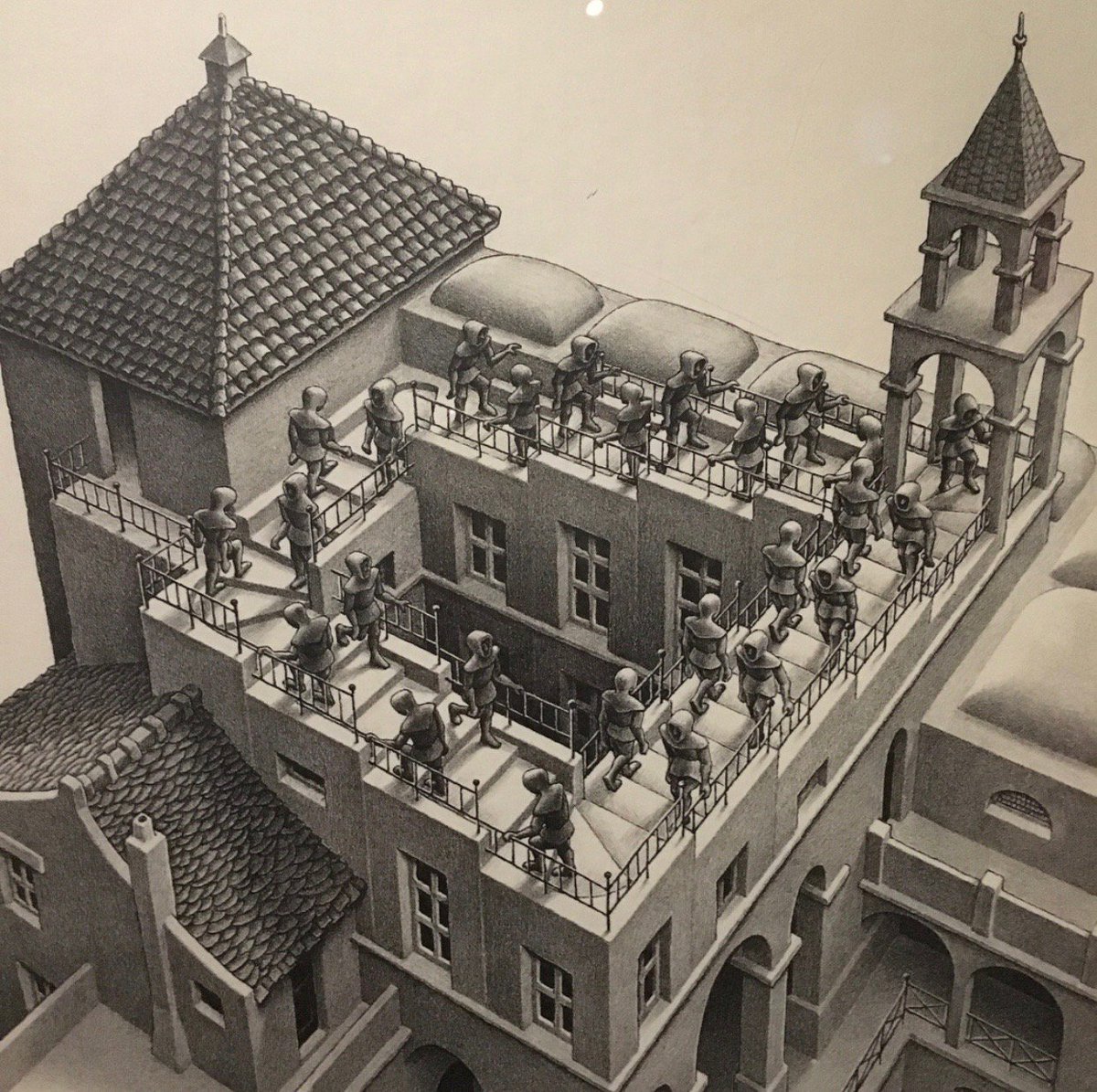

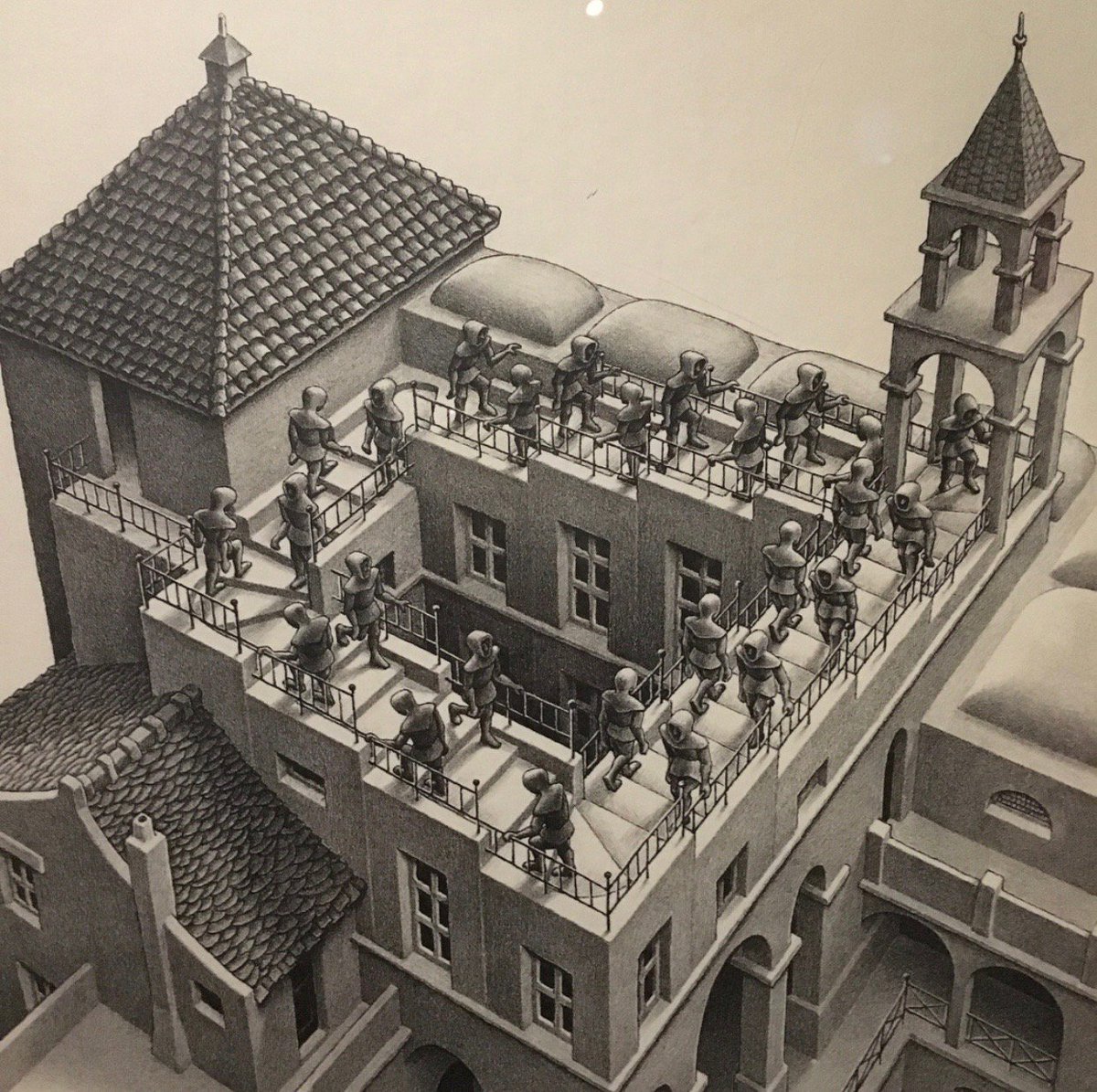

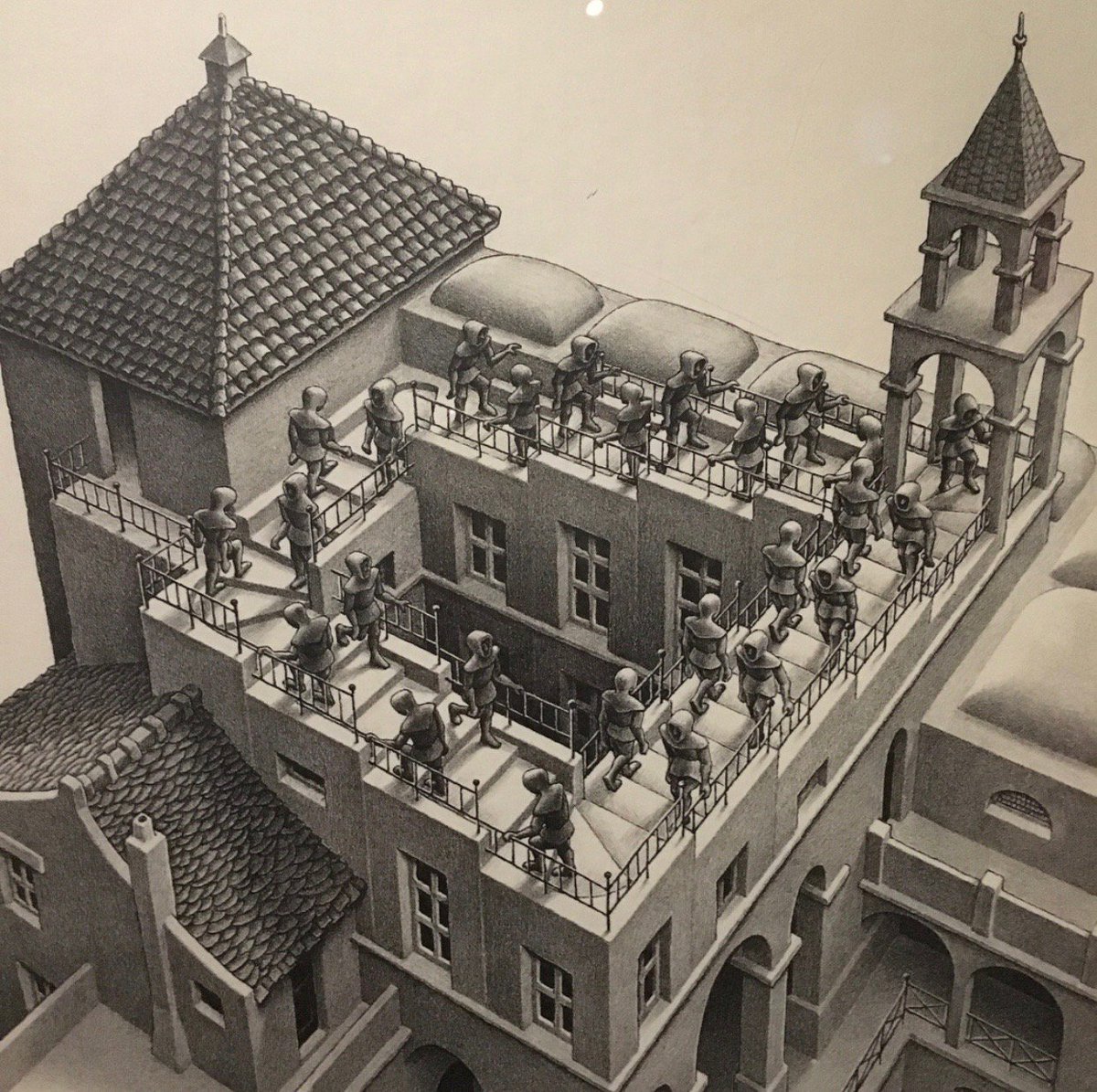

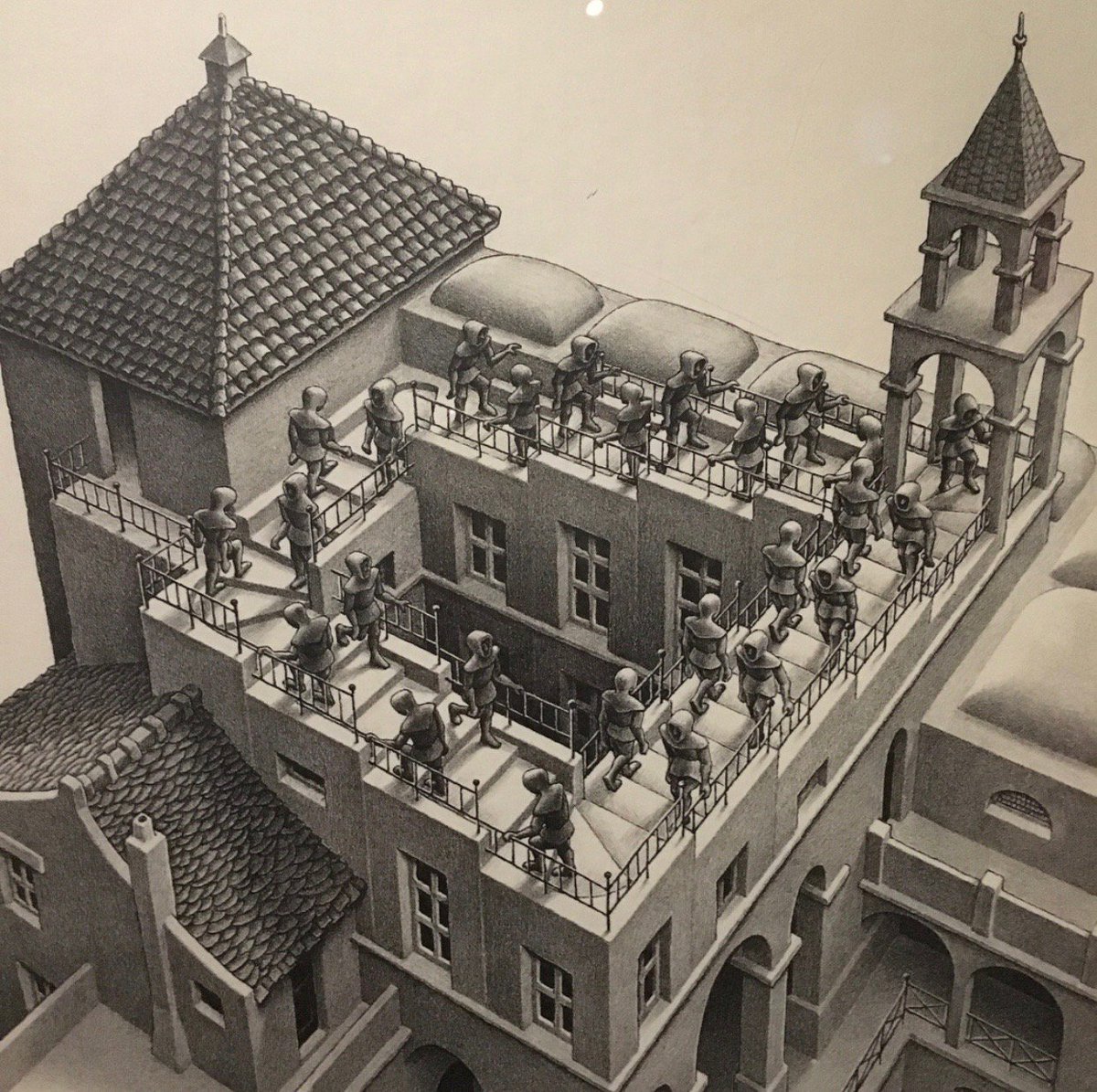

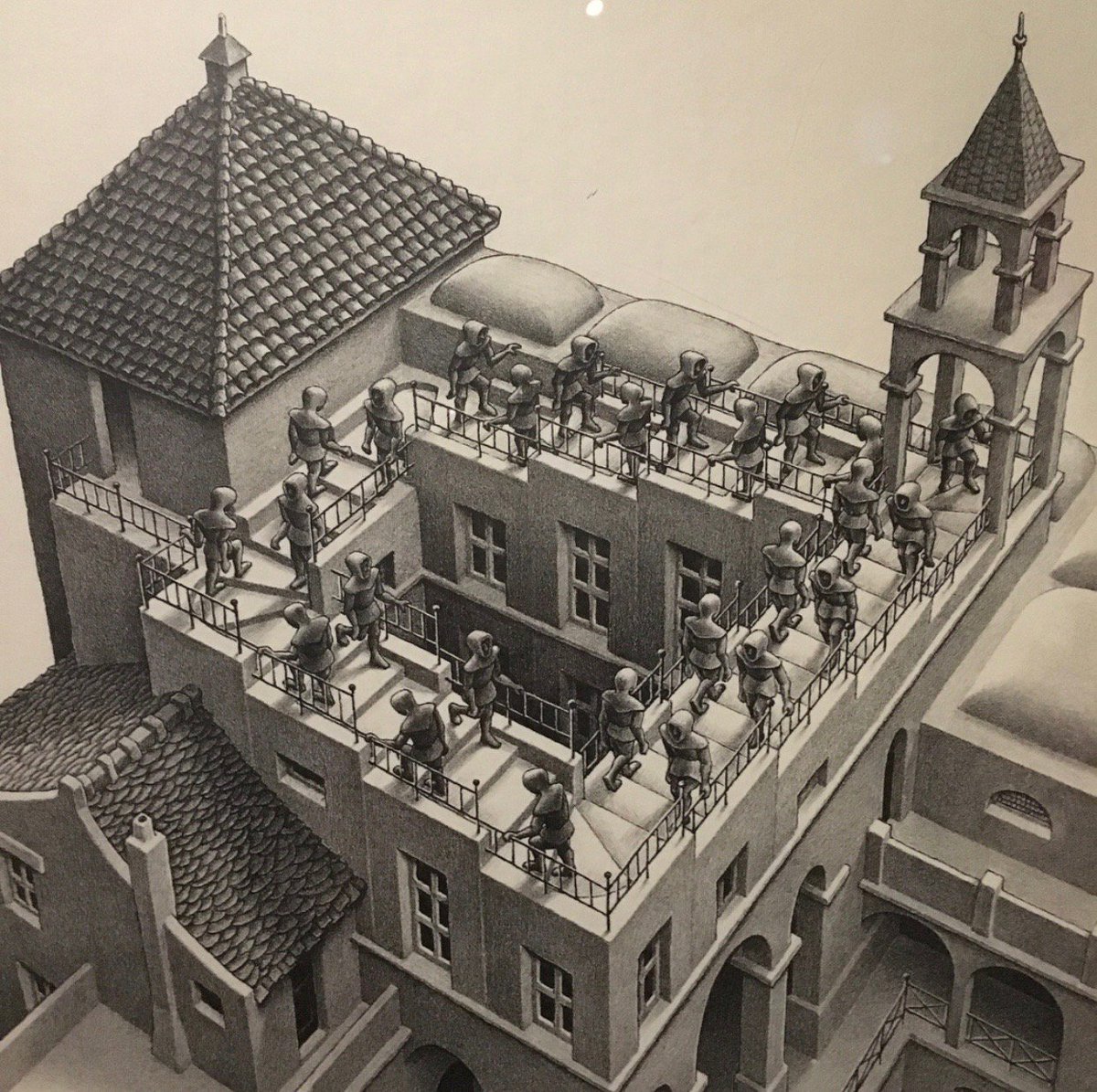

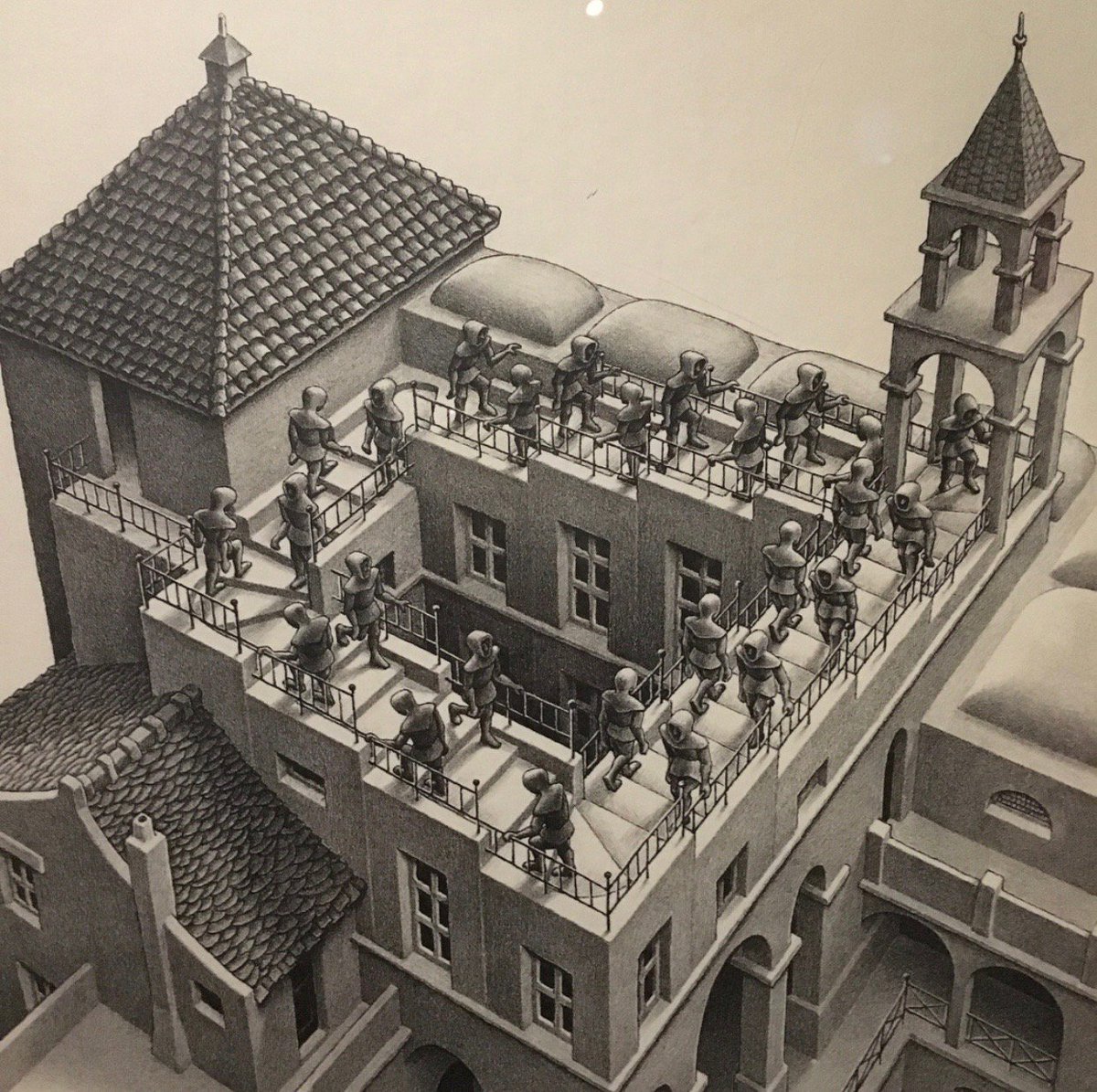

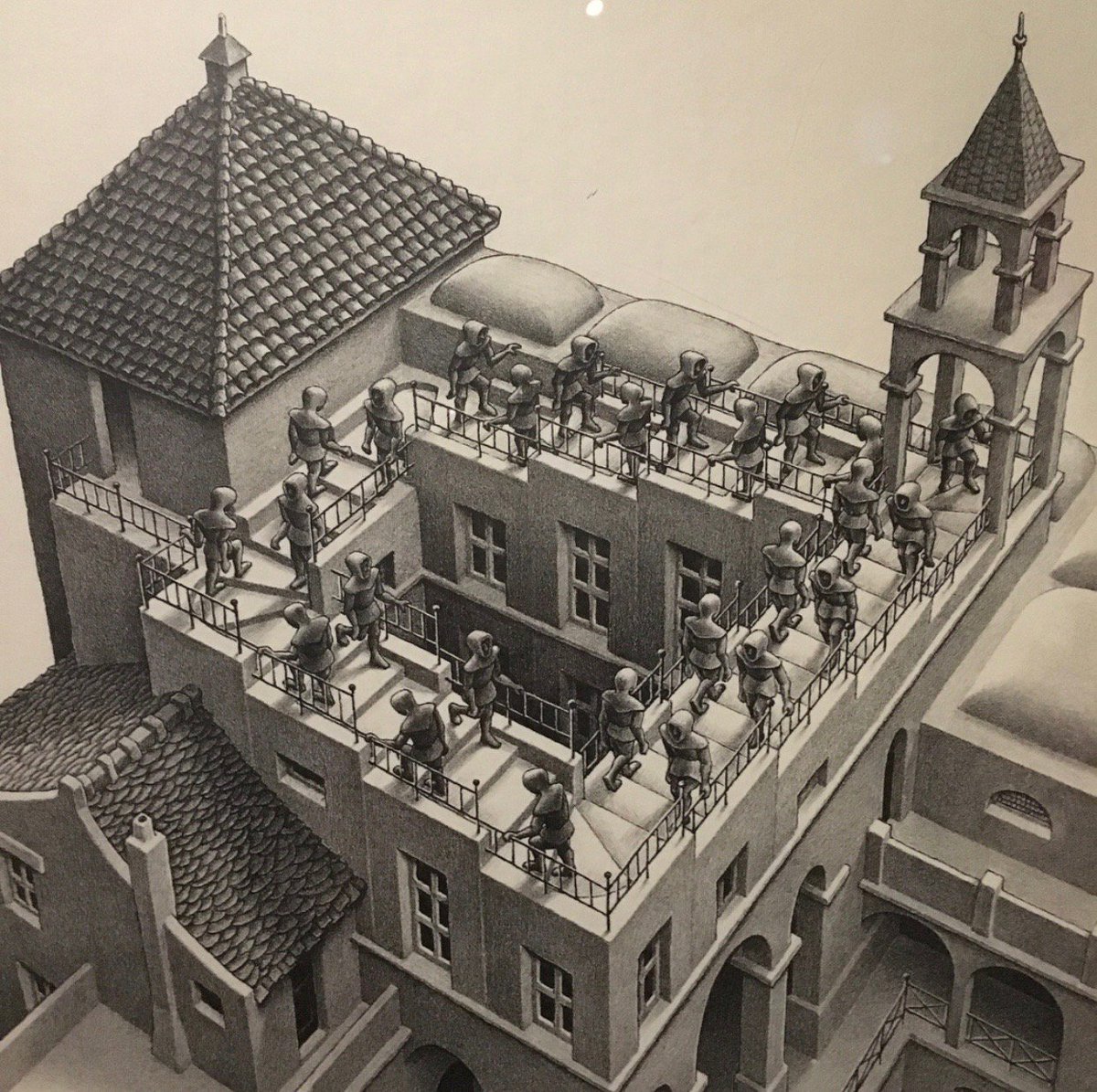

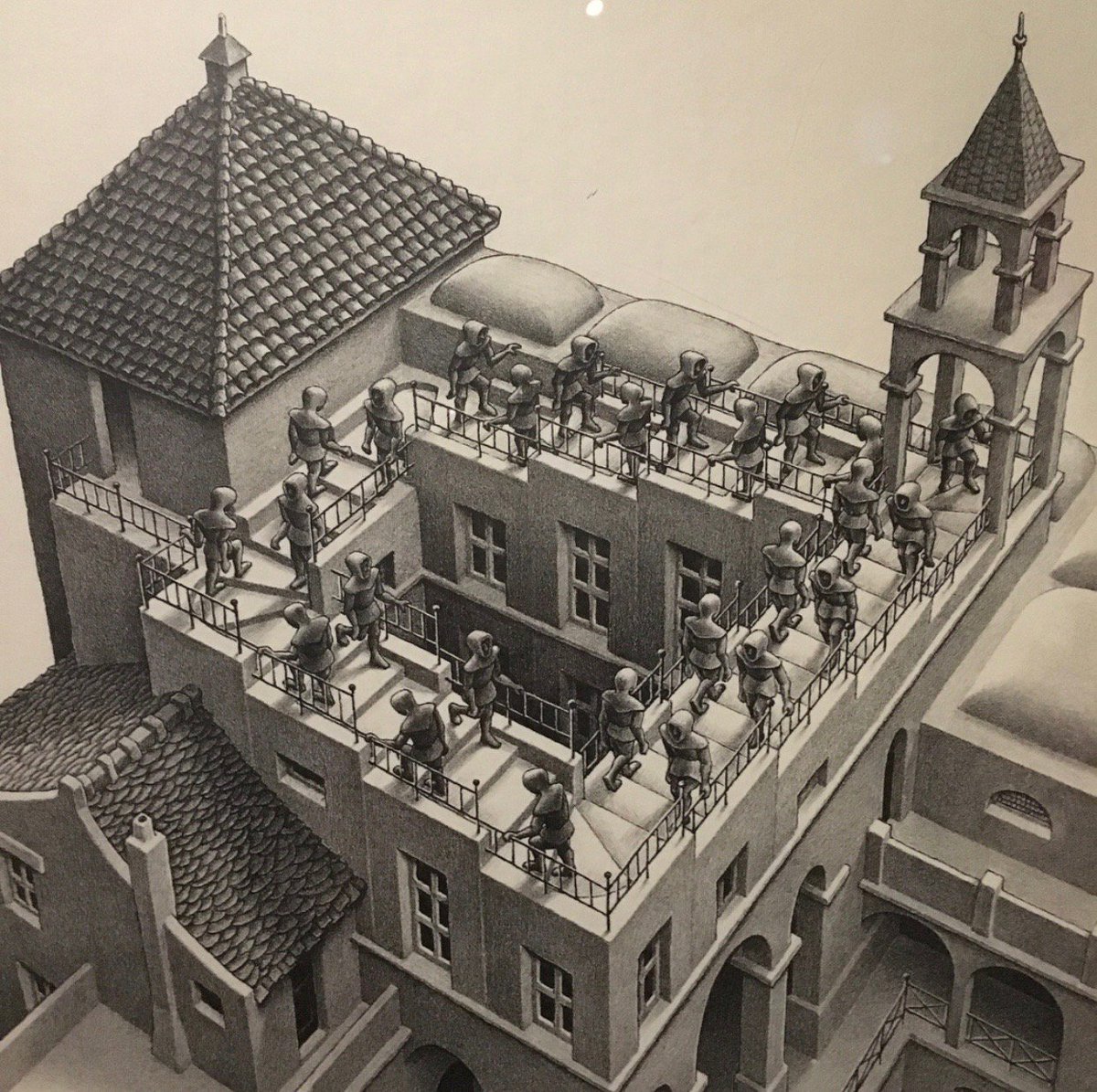

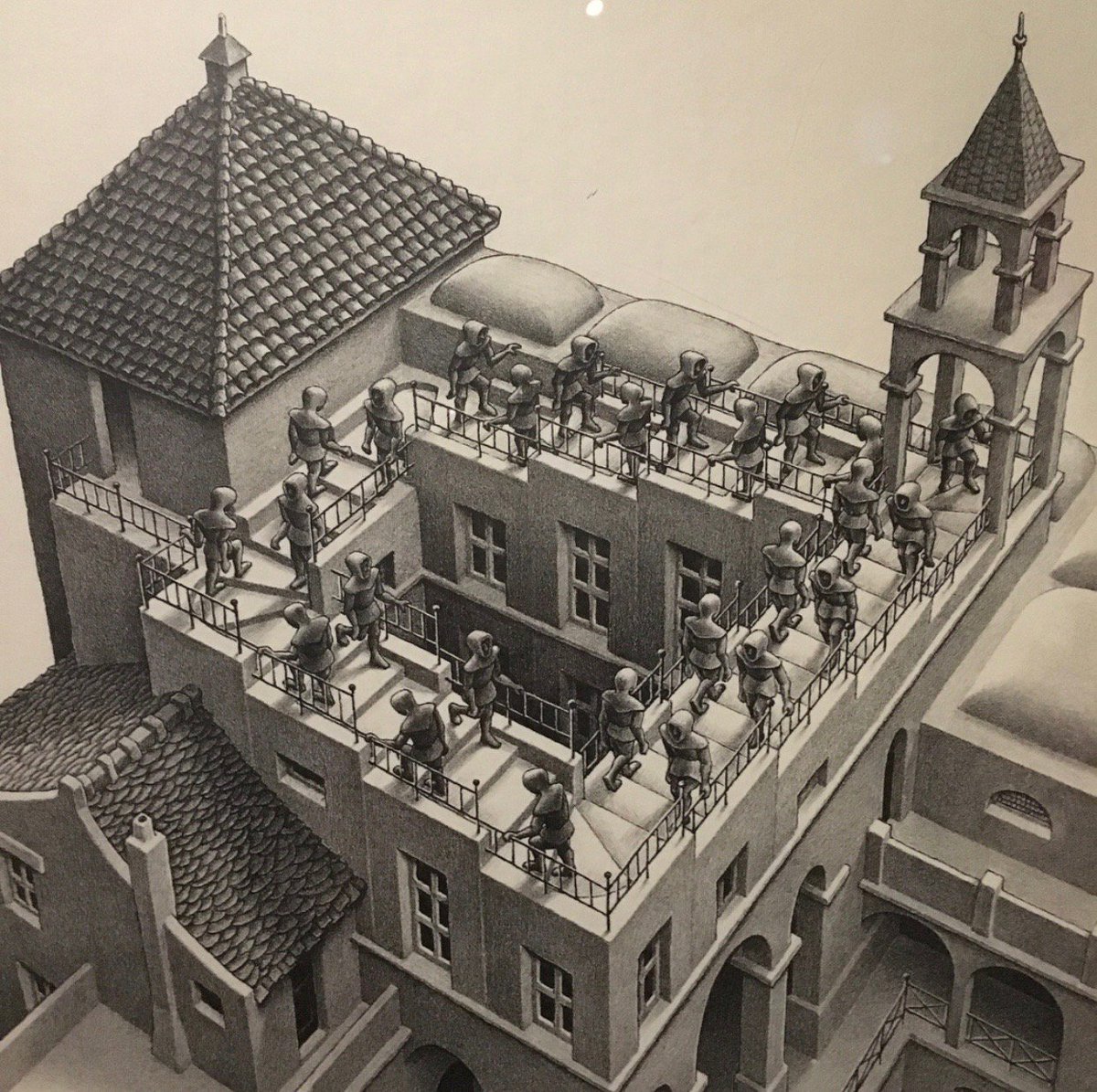

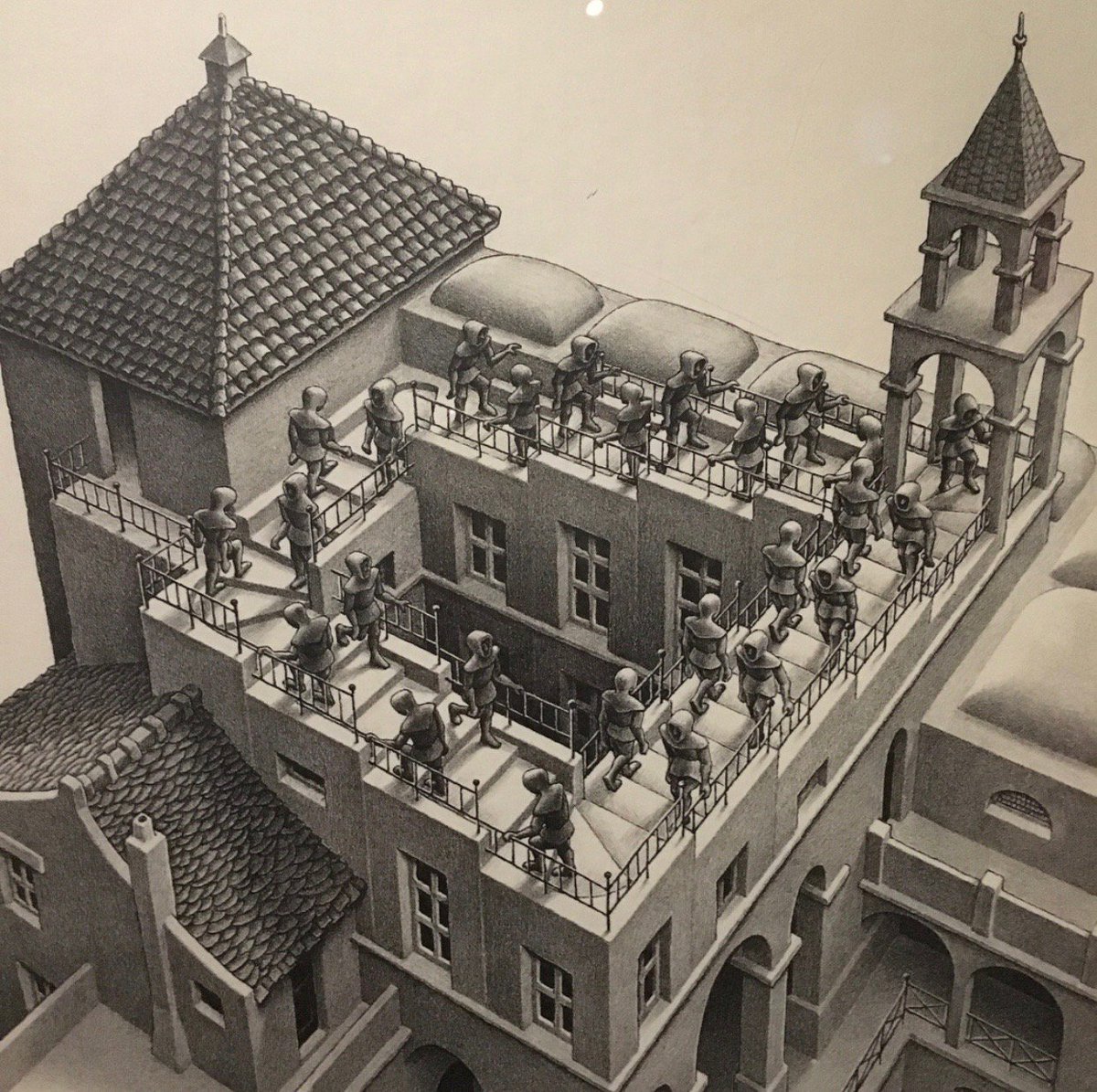

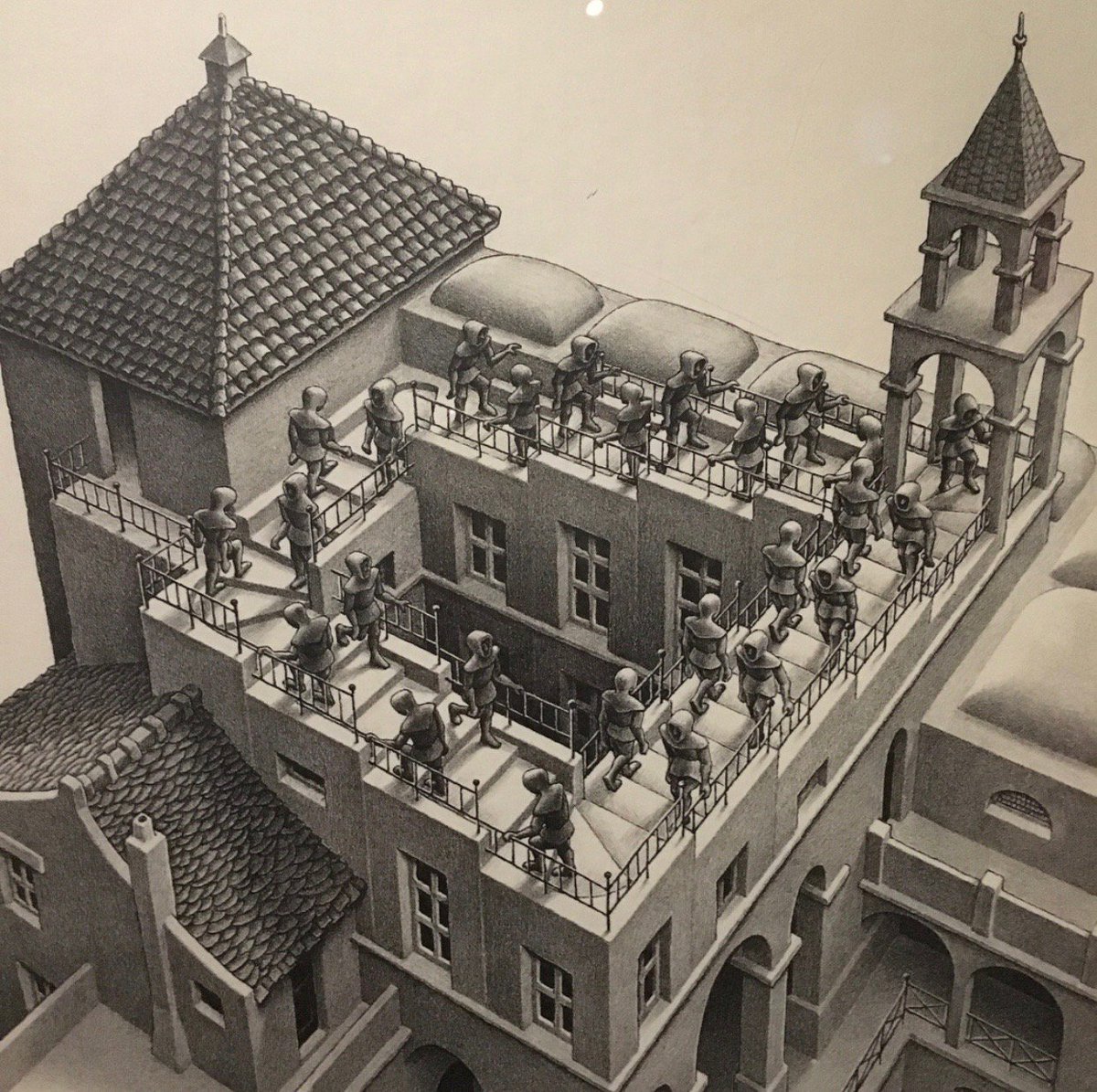

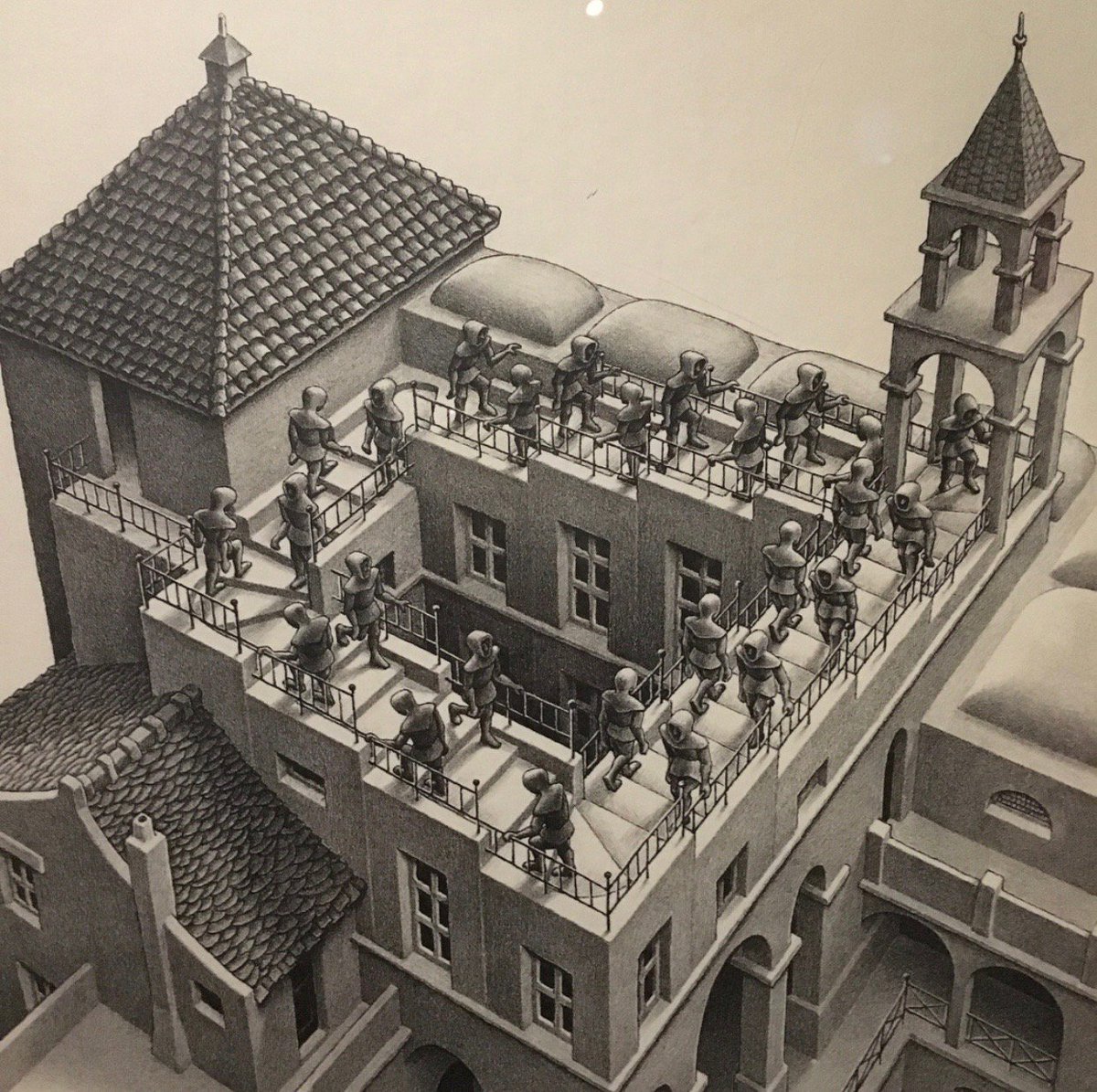

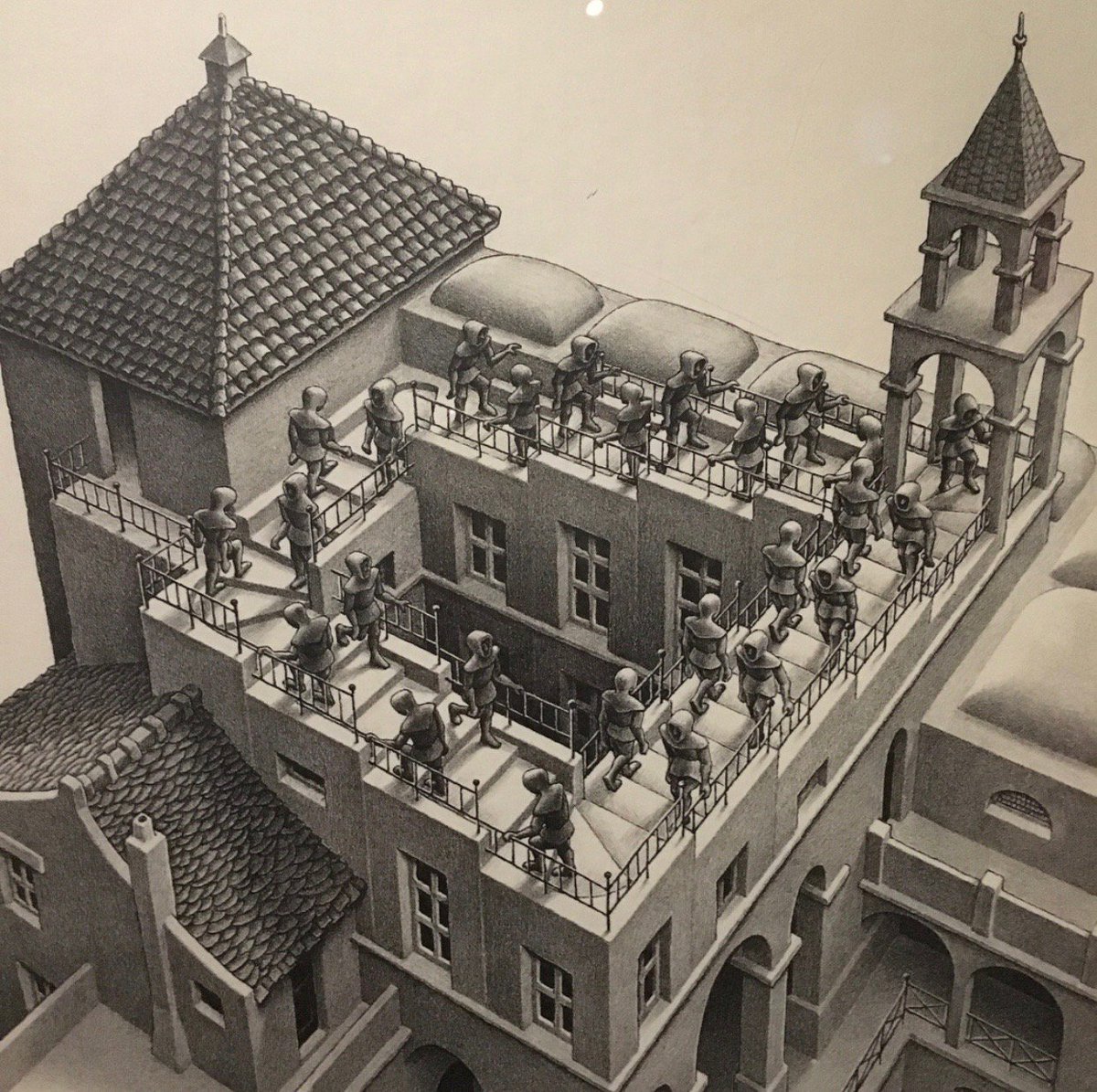

Which brings us back to the flair of Roger Penrose. The Nobel laureate displays a visual bent in much of his work. It was Penrose’s tribar, the impossible triangle he devised in the 1950s, that inspired MC Escher’s optical illusion of the ever-ascending staircase. At the London Institute for Mathematical Sciences, where I work, our hallway is decorated with the beautiful aperiodic pattern of Penrose tiles. The very essence of theoretical science, Penrose explains, is “the aesthetic, the joy, the beauty in the subject itself, that elegance which lies in a proof or a result”.

Presenting theoretical science as an art form is not an intellectual sleight of hand. It helps us see the structural connections between art and theory. Nor is the price tag large. From the government’s perspective, one of the most attractive things about theory should be how cheap it is. Experiment requires equipment, which is expensive to buy, house and maintain, and the costs continue to soar. When Ernest Rutherford discovered the nucleus, he was the only author on the paper. One hundred years later, the paper that heralded the elusive particle known as the Higgs boson had 2,933 authors.

Even a small shift in research funding allocation would have a big effect on the power and prestige of British science. This current government has already committed to increasing the R&D budget to 2.4% of GDP over the next seven years, a hike to its highest level since the 1980s. But if Britain is to be a world leader in science, the government will also need to redress the funding imbalance between experiment and theory. Boosting the fraction that goes to theory will be the best way to salute the artistry of Penrose and his forebears, and support the theorists of the future.

Dr Thomas Fink is the Director of the London Institute for Mathematical Sciences.

LCP